|

body {

// background-color: black;

background-color: #363142;

color: #FFFFFF;

font-family: Trebuchet, Arial, sans-serif;Arial, sans-serif;

//background-image: url('http://www.kundskabenstrae.dk/top-filer/main_bgfixed.gif');

// background-attachment: fixed;

}

h1 {

color: #edc487;

font-size: 4;

font-family: Trebuchet, Arial, sans-serif;

font-size: 400%;

}

h2 {

color: #ffffff;

font-size: 3;

font-family: Trebuchet, Arial, sans-serif;

font-size: 300%;

}

h3 {

color: #edc487;

font-size: 3;

font-family: Trebuchet, Arial, sans-serif;

font-size: 300%;

}

h4 {

color: #ffffff;

font-size: 2;

font-weight: bold;

font-family: Trebuchet, Arial, sans-serif;

font-size: 200%;

}

h5 {

color: #ffffff;

font-size: 1;

font-family: Times New Roman, Arial, sans-serif;

font-weight: italic;

// line-height: 1.6;

}

/*

strong {

font-weight: bold;

}

*/

|

|

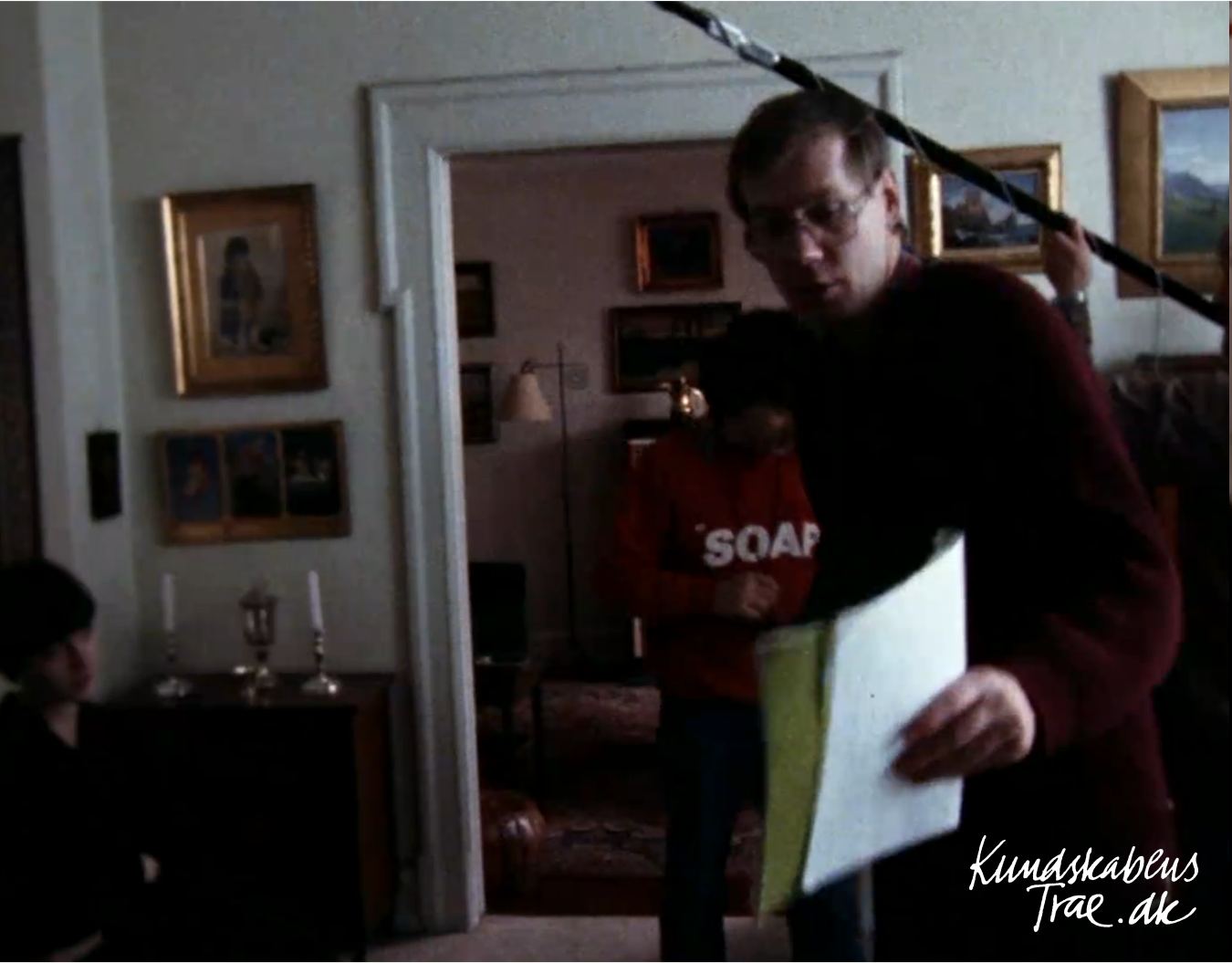

| Life Stories The autobiographical films of Nils Malmros, Danish cinema's best-kept secret

olaf's world

by OLAF MOLLER

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

FOR OVER 20 YEARS, NILS MALMROS HAS BEEN IN THE HABIT OF announcing each new film as his final work. He would explain that he'd exhausted everything in his personal experience that might interest an audience - and that since cinema was his passion and not his profession, he'd rather quit than betray it by making more films. But there was one story he longed to tell, traces of which appear in his films since Pain of Love (92), but which seemed an impossible undertaking - even though it continued to haunt him. No wonder, as the story in question described a personal catastrophe: the killing of his baby daughter by his wife during a psychotic episode.

Last year Malmros finally managed to bring himself to put these events on film. Sorrow and Joy (13) begins with filmmaker Johannes (Jakob Cedergren), the eighth (so far) of Malmros's onscreen alter egos, returning home from delivering a lecture to find his parents stricken with grief. It isn't until close to the end of Sorrow and Joy that Johannes's wife Signe (Helle Fagralid) describes exactly what happened while he was away, answering a question that has gone unspoken for decades. Johannes then tells her that he can't imagine making a film about what happened because he wouldn't be able to bear depicting the traumatic central event. The film concludes - in a flashback -with him driving off to said speaking engagement.

The subject of Sorrow and Joy isn't infanticide - it's about how one man tries to save the woman he loves, and how society helps him. At the core of the film is a long discussion between Johannes and Signe's court-appointed psychiatrist, Birkemose (Nikolas Bro). Ready to commit her to a mental institution, Birkemose nevertheless listens to what Johannes has to say, if only as a courtesy; managing to find the right words to tell Signe's story, Johannes changes Birkemose's mind.

Despite the Malmros family's fame in Denmark, only a few family members, officials, and doctors were familiar with what happened that afternoon in 1983. The court case was heard in closed session, and what was disclosed to the media was phrased in the most general terms possible in order to shield the couple; as a result, after her recovery, Malmros's wife was able to return to her job as an lower-school teacher. It was only when Sorrow and Joy's production was announced in 2012 that the public learned the facts - or could surmise them, because of the well-known autobiographical bent to most of Malmros's films.

THAT SAID, THE AUTEUR'S ALTER EGO isn't always necessarily the protagonist of his films. In his school-memoir master-piece, Tree of Knowledge (81), and its sort-of sequel, Aching Hearts (09), Malmros's stand-in is a secondary character who loses the girl to the same guy in both films; similarly, in Pain of Love, Malmros's film about his wife's life before she met him, he is a secondary presence; and Facing the Truth (02) is about his father, an internationally renowned neurosurgeon, whose son is present in several scenes but never identified. In fact, only Sorrow and Joy and Arhus by Night (89), his return to filmmaking after the tragedy, are centered firmly on him. As for Lars Ole, 5c (73) and Boys (77), the films that made his name, Malmros drew upon his boyhood memories and feelings without re-creating actual events.

For Malmros, this autobiographical impetus is essential. He aims to make his films as true to his life experiences as is possible - and prudent - with minor alterations to make the narrative flow more smoothly, underline a character's particularities here, or reinforce a certain theme there. Because he is often invited to talk about his work in schools, Malmros has even prepared a DVD containing materials that reveal how close to life the films are. For example, there's a file on the Tree of Knowledge disc containing a slide show of images from the film and photos from Malmros's school days demonstrating that the actors were cast according to their resemblance to their real-life inspirations. Well, yes and no: it's telling that Eva Gram Schjoldager who plays Elfin, the girl who's ostracized by her class, has more stereotypical "Jewish" looks than the "original" Elfin - whose Jewishness was, per Malmros, unknown to him and his classmates. He subtly reinforces that angle in the film without ever dealing with it explicitly - anti-Semitism isn't the subject of Tree of Knowledge, it's just a thematic undercurrent. Elfin is persecuted for brusquely rejecting the amorous advances of a boy, who takes his revenge by bad-mouthing her so effectively that her peers turn against her; her Jewishness is neither acknowledged nor concealed, and therefore at some level it's known. The kids are most likely reacting subconsciously, reflecting how certain prejudices can lurk just below society's enlightened surfaces.

What makes Tree of Knowledge so great is its portrayal of youth: what it means to be at the threshold of adulthood, cross the straits between innocence and experience, and in some cases drown in a sea of rejection and disappointment. It's something that the film's participants - one hesitates to call them actors - experience for themselves during the film's production, right before our eyes. Tree of Knowledge, as well as Aching Hearts, has a primarily amateur cast, and was shot over the course of several years so that the youngsters could develop with their roles; and in that respect these films are small-scale precursors to Boyhood. But where Linklater seems to discover his protagonist's experiences right alongside him and everything feels fresh and new, Malmros confronts situations in a way that says these are neither the first nor the last kids who'll grapple with these anxieties and yearnings. Accordingly, he treats his actors, in a vaguely Bressonian fashion, as models, vessels for truths that they themselves may be unaware of. Starting with Lars Ole, 5c and ending circa Beauty and the Beast (83), Malmros preferred to shoot comparatively brief takes with a mostly static camera. He rarely explained a scene to his actors: if they had to say something, they were given their lines just before the camera rolled; if he needed non-verbal behavior, he would come up with things for them to react to. What counted was that the camera capture people doing something for the first and maybe only time. This is what makes his earlier works so mesmerizing: while the characters learn life lessons, the actors remain in a state of perpetual innocence.

IF THERE'S A DRIVING FORCE TO MALMROS'S cinema, it's sex. The kids in Lars Ole, 5c and Tree of Knowledge, as well as the protagonists' younger selves in Boys, sense the fleshly pleasures awaiting them, but have no inkling of what they mean and entail; the older youths in Boys and the teenagers in Aching Hearts have already had a taste and want more - and face the conse-quences, ranging from shattered illusions to pregnancy. Beauty and the Beast depicts a 16-year-old girl and her father lost in their respective no-man's-lands. She's not quite an adult yet and he's no longer young - but he suddenly finds his parental feelings and pangs of hebephile desire becoming difficult to tell apart, while for her, kindness, love, and desire too often feel alike. Arhus by Night, Malmros's only all-out comedy, is a whimsical fantasy about the making of Boys in which the shoot becomes a sexual free-for-all while shy director Frederik gets lost in the erotic reveries he's trying to capture on film. And Barbara (97), the director's lone excursion into literary adaptation, is a big-budget heritage cinema outing set on the Faroe Islands in the 18th century that recounts the passion of a pastor for the lusty widow of his two predecessors. While the island community is held together by piety, it needs a certain level of promiscuity to maintain its population; when a French man of war anchors in the harbor, a fête in honor of the sex-starved sailors devolves into an orgy. The local menfolk grimly accept the need to replenish the gene pool, struggling with feelings of jealousy that these people at the edge of the world can ill afford. J

ealousy, Sorrow and Joy implies, was also a factor in its tragic scenario. During the making of Tree of Knowledge, Malmros became infatuated with one of the girl performers, Line Arlien-Soborg; he decided to make Beauty and the Beast with her in order to confront his confusion and desire; for proper distance, he projected his feelings onto a situation he deemed appropriate. Malmros's wife sensed that something was going on - as chronicled in Pain of Love, painful experiences had destroyed her trust of men. The opening titles of Beauty and the Beast end with a dedication to Malmros's newborn daughter ("To Anne") under an image of Arlien-Soborg lying apparently naked on a duvet staring straight into the camera.

The same dedication suggests closure when it appears in the end credits of Sorrow and Joy, a film that had been with Malmros and his wife for 30 years. And now Malmros acknowledges that he has managed to do something of which he believed himself incapable: explore requited love. Over the years he had come to believe that love was only real when it remained unrequited - pure and unrealized. With Sorrow and Joy he has created one of the most shattering and elevating expressions of love in film history.